Always Changing

“I’ve always thought that Scotland’s popular history is just like her landscape—impossibly romantic, obscured by mist and myth, and always changing.”

On our way to church this fine, cold Sunday morning (Dec 11), we walked out our front gate and found this “dime” lying there. It’s technically 5 pence, but, hey, it sure looks like an American dime!

Many of you reading may be surprised by the frequency with which we have been attending church in Edinburgh, given our history of abstinence at home. However, some of us have talked widely about this and will know that it has not been a rejection of God or church but the choice by most evangelical churches to draw sustenance from a deep well of clichés and isms, and the fervent obsession with a narrow range of doctrines, to the exclusion of virtually all others.

I wish I had taken this! It’s from their webpage.

Our experiences at St Giles Cathedral have been a refreshing and reinvigorating reassurance that church can still be surprisingly relevant. Despite the antiquarian setting, this Sunday’s sermon (39 minute mark) offered contemporary application of the Christmas story. The minister made wonderful sense of Matthew’s intention behind presenting Jesus’ lineage, hypothesized on the inclusion of the particular women mentioned in the genealogy, and did not shy away from inconsistencies in the Gospel narratives. It was a deeply thoughtful and well-reasoned message that offered honest and realistic application for our daily lives. Perhaps it is not surprising that the minister delivering the sermon was a woman. We’re very grateful for time spent at St Giles Cathedral; it has made our Edinburgh experience even more meaningful.

Dad, you may recall I mentioned in my reply to your comment that the St Andrew’s Cross (Saltire) was ubiquitous in Scotland; well, it’s literally etched into every seat inside the cathedral.

After church, we looked through a few shops on the Royal Mile and wandered into Brodie’s Close.

Deacon Brodie is believed to be the real-life inspiration behind Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: a duplicitously skillful cabinet-maker and member of the Town Council by day and leader of a gang of burglars by night.

This image shows some amazing old world character from inside Brodie’s Close, where Deacon Brodie lived. Check out the amazing iron adornments on this wee door.

Brodie’s activities were eventually discovered and he escaped to the Netherlands, but was arrested in Amsterdam and returned to Edinburgh for trial.

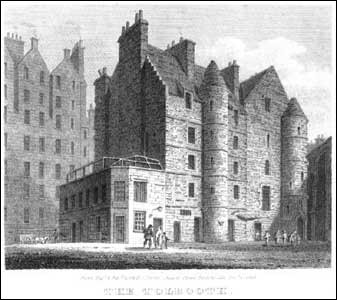

Brodie was kept at the Old Tolbooth that used to stand just outside St Giles Cathedral.

Brodie was hanged on the gallows platform at the Tolbooth in 1788.

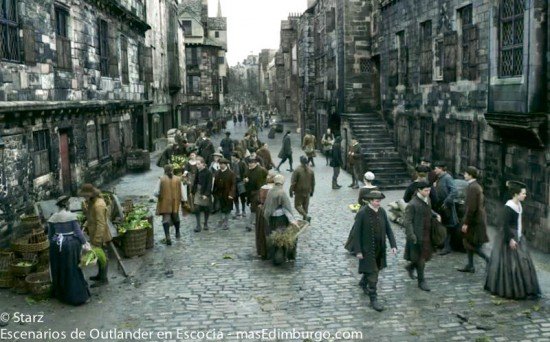

You may recall that the Heart of Midlothian marks the main entrance to the notorious former Old Tolbooth jail. The real life Deacon Brodie likely entered here before being tried, convicted, and hanged. Likewise Jamie Fraser’s men were locked in the same jail in Outlander.

While Brodie was clearly guilty, the Heart represents the many far more innocent souls (like the so many Jacobites) who found punishment and death inside the infamous Old Tolbooth. The gold brick is one of several that mark the perimeter of the old tollbooth.

Monday

The Bearded Baker, always a great way to start off the new week.

On our way to The Scottish Parliament Building on Monday (Dec 12), we entered the nearby New Calton Burial Ground. Opened in 1820, the graveyard came complete with a watchtower to guard against grave robbers, known as “resurrectionists.”

The fear of your loved one's body being dug up in the dark of night and sold for anatomical dissection was considerable in Edinburgh, because the city had become the world leader in the study of anatomy. The medical schools needed bodies and paid good money for them; until 1832, the only bodies legally available were those of executed criminals—a paltry 55 a year. The schools needed ten times that. All sorts of deterrents to disinterment were employed: extra deep burial, locked cages over the graves, coffin collars which secured the corpse to the base of the coffin, locking iron coffins called “mortsafes” (pictured in our Greyfriars Bobby post from December 5), and overnight guards stationed in watchtowers like this one.

In December 2022, the graveyard is a peaceful place with a view of the Palace of Holyroodhouse and the Scottish Parliament Building. Arthur’s Seat is in the distance with the sun rising just above Salisbury Crags. It’s 11:30 and that’s as high as the sun has made it.

We joined the free 11:30 tour of the Scottish Parliament Building. Scotland is obviously part of the UK—which consists of England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. However, Scots do debate and make many local laws that pertain exclusively to Scotland (“devolved” matters—some of which require Crown consent). Of course, the Parliament of the UK is the supreme legislative body of the UK, and it meets at the Palace of Westminster in London, and only they can set laws on “reserved” matters.

The Debating Chamber is where all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) meet to debate and make decisions.

This ceremonial silver and gold Mace (inside the glass enclosure), symbolizes the power of the Scottish Parliament to pass laws. It also explores ideas about the relationship between the Parliament, the people of Scotland, and the land. It is made from silver and gold panned from Scottish rivers. The head of the Mace features words from the 1998 Scotland Act that created the Scottish Parliament, “There shall be a Scottish Parliament - The Scotland Act 1998.” It was presented by Her Majesty The Queen at the opening ceremony of the Scottish Parliament on July 1, 1999.

On the inlaid gold band are the values of compassion, wisdom, justice, and integrity. These are presented as the characteristics that people should look for in their elected representatives.

Just a good ol’ fashioned gavel—no special Scottish name, except that it is used by the elected Presiding Officer (PO), who is currently Alison Johnstone MSP, the first woman to hold the position.

The Scottish Parliament was only established in 1998 and will celebrate its 25th anniversary next year, so it is a relatively new legislative body. Which means it is also a relatively new building in a city full of some of the world’s oldest buildings. If you haven’t noticed already, the building is famously (or infamously depending on your point of view) modern in design.

As with the old religious buildings in the city, there is symbolism throughout the design. The design on the desks above represent nature (Scots obviously feel a deep connection to the land).

The overhead lights bear a modern symbolic interpretation of the bodies of people, and their number represents the number of SMPs who represent the people.

We weren’t allowed to take photos in most places, but here is a picture from a post card that shows the design as seen from inside the building.

Outside it looks like this and…

Here’s an aerial perspective from the inter-google-webs. People seem to either love or hate the building: a post-modern masterpiece or a blight. Also, due to mismanagement, the building ultimately cost 10 times the original price tag. (Surprisingly, they didn’t mention that during the tour. 😆)

So, Amanda’s final verdict? 1.5 out of 10.

Despite my previous rant on the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, I still gave the building itself a solid 7. It is very much “incongruous” as I said on a different post, but it does have a lot of function in the design.

Amanda’s perspective on my 7 rating?

Now that’s just disrespectful!

I just happened to see the Historical Landmark icon on Google Maps for White Horse Close. Apparently the famous White Horse Inn (borrowed by Gabaldon as Whitehorse Tavern) was once located at the north end of the close—the name taking inspiration from Queen Mary and her favorite steed. The pub closed its doors in the late 18th century and the courtyard at some point was renamed White Horse Close.

Eventually, this courtyard was renovated as part of the “slum clearance” of Canongate during the 1950s. Although it was renovated, it wasn’t rebuilt authentically. As such, many historians dislike the updated design. Other than the quote from Voyager above, I don’t believe the close was used for filming.

Amanda in White Horse Close

The coach debouched into a yard at the back of Boyd's Whitehorse tavern, near the foot of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh...

—Voyager, Diana Gabaldon

Continuing up the Royal Mile, Amanda happened to see a sign for Dunbar’s Close Garden, so we wandered down the close. A surprisingly lovely hidden garden.

Despite the frosty late autumnal weather, the garden was still quite beautiful.

Walking up to the Tolbooth Tavern is this set of stairs, easily recognizable from Outlander Season 3.

Since we were there, we stopped in the Tolbooth Tavern for a pint of Guinness and some fries. We have learned that they sometimes still call the fries above “fries” and reserve the term “chips” for their larger, wedge-cut cousins.

The Tolbooth Tavern is part of the original Canongate Tolbooth which was built in 1591. Anytime you can drink a pint in a 431-year-old building, ya do it!

The Tavern is relatively new to the building, but it’s still over 200 years old!

Tomorrow (Dec 13) we descent into the underground to explore the parts of Edinburgh that are so old, they lie under the present-day streets. Can’t wait!