The Brontës

“I’ve dreamt in my life dreams that have stayed with me ever after, and changed my ideas: they’ve gone through and through me, like wine through water, and altered the colour of my mind.”

In front of Haworth Parsonage.

The site of the old gate leading to the church used by the Brontë family, and through which they were each carried to their final resting place in the church.

The Brontë family came to live at Haworth Parsonage in 1820 when Patrick Brontë was appointed Perpetual Curate of Haworth Church. He brought with him his Cornish wife, Maria, and their six young children.

Theirs is a tragic story. Mrs Brontë died within eighteen months of their arrival and her sister, Aunt Elizabeth Branwell, moved into the Parsonage to help with the running of the household.

In 1825 the two eldest Brontë children, Maria and Elizabeth, also died after contracting tuberculosis while away at school.

For the remaining members of the Brontë family, the Parsonage was home for the rest of their lives. Patrick Brontë outlived all his famous children, dying here in 1861 at the age of 84.

Mr Brontë’s Study—Mr Brontë carried out his parish business and gave his children lessons here.

Education had enabled Mr Brontë to advance in the world and he fostered his children's interest in literature, politics, art, and music.

He purchased the cabinet piano, which was mainly played by Emily and Anne, and decorated the study walls with engravings of biblical scenes by John Martin. Martin's works were an early inspiration for the young Brontës.

Dining Room—Charlotte, Emily, and Anne did much of their writing here. Their world famous novels Jane Eyre (Charlotte), Wuthering Heights (Emily), and Agnes Grey (Anne) were written in this room. At night, the sisters would walk around the table discussing their writing. By the fireplace stands the rocking chair where Anne would sit with her feet on the fender.

A reproduction of the famous portrait of Charlotte by George Richmond hangs above the fireplace. After Emily and Anne died, Charlotte was left to walk in solitude.

It is believed that Emily died on the sofa in this room. A plaster medallion portrait of their only brother, the ill-fated Branwell Brontë, hangs above the sofa.

If you watch the movie Emily (2022), you will see that they either filmed some scenes in the museum or very faithfully recreated this room and the one above.

Kitchen—The Brontë sisters were expected to take a share of the household tasks, and after Aunt Branwell's death, Emily acted as housekeeper while Charlotte and Anne worked away from home as governesses. Baking bread or ironing allowed Emily the mental freedom to focus on her writing, and she was always happiest at home.

In the Brontë’s time there was a back-kitchen where the washing and heavier household work would have been carried out. This was demolished in 1878 to make way for a large kitchen extension which was added to the Parsonage by Mr Brontë's successor, John Wade.

Throughout 2017, artist Clare Twomey invited visitors to the Brontë Parsonage Museum to recreate the long lost manuscript of Emily Bronte's masterpiece, Wuthering Heights.

In the making of this handmade book, almost 10,000 visitors were invited to copy it down one line at a time, writing in the house where Emily wrote her famous novel.

The completed manuscript is now on display, to celebrate the bicentenary of Emily's birth (July 30, 1818). This re-creation honors Emily's achievement and celebrates her contribution to English literature through the act of writing.

Each evening at nine o'clock, Mr Brontë would lock the front door and call in at the dining room to warn his daughters not to stay up too late. On his way to bed he would stop to wind this grandfather clock made by Barraciough of Haworth.

Anne, Emily, and Charlotte Brontë, c. 1834 by Branwell Brontë—This is a copy of Branwell's painting of his sisters which is now in the National Portrait Gallery, London. At first Branwell decided to include himself in the portrait but later painted himself out, though his shadowy figure can still be seen between Emily and Charlotte.

Arthur Bell Nicholls, Charlotte's husband, took the painting back to Ireland with him, where for many years the canvas lay folded in a cupboard.

There are very few contemporary portraits of the Brontës in existence and this is the only known painting of the sisters together.

This room was originally used by Mr and Mrs Brontë. After Mrs Brontë's death in 1821, it was taken over by her sister, Elizabeth Branwell, who took charge of the running of the Parsonage and taught her nieces sewing and other household accomplishments.

Aunt Branwell died in 1842 and thereafter, the room is likely to have been used by different members of the family.

When Charlotte married she and Arthur Bell Nicholls shared the room, and it was here Charlotte died in 1855, with her husband praying at her bedside. Today the room is used to display Charlotte's clothing and personal treasures.

Emily Brontë's Artist's Box from 1827—I thought Erica and any other artists out there might appreciate it.

Emily Brontë's Writing Desk—Each of the sisters had her own portable writing desk. This desk belonged to Emily and is made of rosewood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl. The contents have been preserved as Emily left them and include: sealing wafers, blobs of sealing wax, pen shafts and nibs, and a small envelope containing Clarke's enigmatic puzzle wafers: small gummed labels for sealing envelopes which are printed with acrostics.

Emily Brontë's Diary Paper, July 30, 1841—This diary paper has particular interest not only because of its rarity but also because it is illustrated. Emily has added two tiny sketches of herself in the Parsonage dining room.

The dress worn by Emma Mackey in the 2022 film Emily.

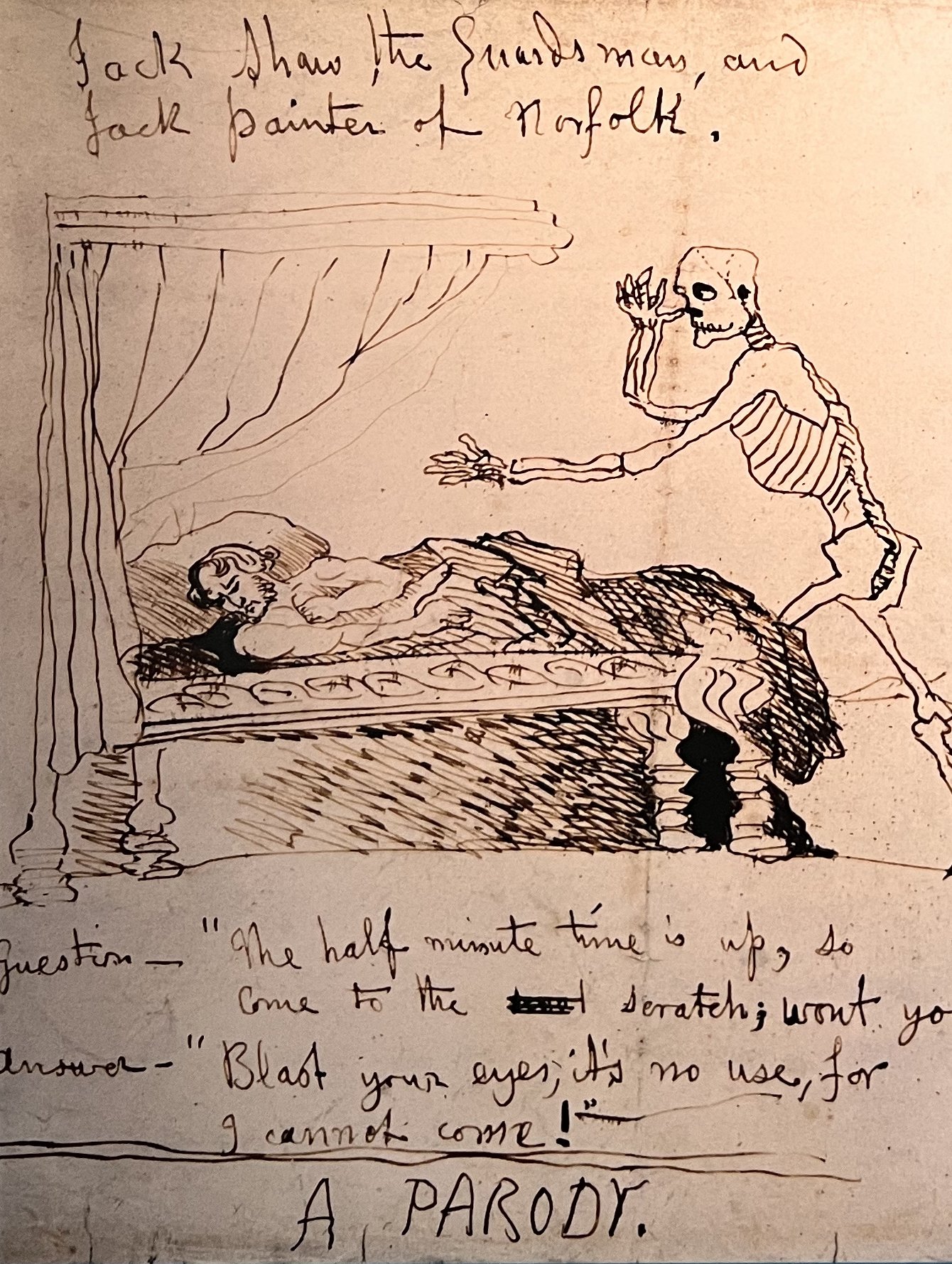

Mr Brontë’s Room—After his wife's death, Mr Brontë moved into this room. None of the original beds have survived. The bed displayed here is a reproduction based on Branwell's drawing of himself being summoned from sleep by Death.

In later years Branwell's addiction to alcohol made him a danger both to himself and his family, his father brought him into this room so that he could watch over him. It was here Branwell died at the age of 31 in 1848, repenting the fact that in all his life he had “done nothing either great or good.”

Branwell Brontë is known to have frequented the Black Bull often and the story goes that when his family were worried he was too drunk, they sent someone to find him. They'd come in one door of the Black Bull and he'd escape via the kitchen window and hot-foot it across the graveyard and into the parsonage before being caught over-indulging on alcohol.

Following research in the Brontë Parsonage Museum collection and using a variety of decorative techniques to reproduce uneven plaster, scuffed floorboards, and chipped paint—Branwell’s Room has been “restored” so as to appear original and authentic, then furnished with antique and replica items relating to his preoccupations and lifestyle at the time.

Names

Patrick Brontë was born on St Patrick's Day, 1777, in a two-roomed cabin at Emdale, in Northern Ireland.

It was not a promising start, but by the age of sixteen Patrick had opened his own school. He was hard-working, ambitious, and saw education as his best means of advancement. In 1802 Patrick entered St John's College, Cambridge, where his ability attracted some influential sponsors including William Wilberforce, the Anti-Slavery campaigner.

It was at Cambridge that he changed his name from Brunty to the more impressive-sounding Brontë. Patrick graduated in 1806 and was ordained into the Church of England. His rags-to-riches story made a profound impression on his children, who were to grow up accustomed to books carrying their family name on the Parsonage shelves

The first Brontë novels were published in 1847, following many years of literary activity beginning in childhood. The sisters concealed their true identities, publishing under the pseudonyms Currer (Charlotte), Ellis (Emily), and Acton Bell (Anne).

“...we did not like to declare ourselves women, because ... we had a vague impression that authoresses were liable to be looked on with prejudice...”

This cupboard belonged to Thomas Eyre of Hathersage, Derbyshire (the Peak District). It was seen by Charlotte when she visited his house with Ellen Nussey in 1845. When she wrote Jane Eyre a year later, Charlotte may have taken her heroine's name from the Eyres of Hathersage. She graphically describes the cupboard in the scene where Jane tends to the wounds inflicted on Richard Mason by Rochester's mad wife.

“I must see the light of the unsnuffed candle wane on my employment; the shadows darken on the wrought, antique tapestry round me, and grow black under the hangings of the vast old bed, and quiver strangely over the doors of a great cabinet opposite—whose front, divided into twelve panels, bore in grim design, the heads of the twelve apostles, each inclosed in its separate panel as in a frame...”

The Brontës: Doomed to an Early Grave, but Fated Not to Die.

Early in 1812, following the deaths of her parents, Maria Branwell traveled from her home in Penzance, Cornwall to Yorkshire to visit her uncle. It was here that she met Patrick Brontë. Following a brief courtship the couple were married in 1812.

Following their marriage, Mr and Mrs Brontë made their home at Clough House, Hightown, where their two eldest children, Maria (1814) and Elizabeth (1815), were born.

In 1815 the family moved to Thornton near Bradford, where the four famous Brontë children were born in quick succession: Charlotte (1816), Patrick Branwell (1817), Emily Jane (1818), and Anne (1820). Shortly after Anne's birth the family moved to Haworth following Mr Brontë's appointment as Perpetual Curate.

Within eighteen months of their arrival at Haworth, Mrs Brontë died from uterine cancer, when the youngest of her six children, Anne, was still a baby.

Her sister, Elizabeth Branwell, had already come from Penzance to care for the family. It was intended to be a temporary arrangement but after Patrick had made three unsuccessful attempts to remarry, she remained at Haworth with the Brontë family.

In 1823 Maria and Elizabeth were sent to Clergy Daughters' School at Cowan Bridge, soon afterwards followed by Charlotte and Emily. The school regime was harsh, and in 1825 Maria and Elizabeth were sent home in ill-health. They died within a few weeks of each other, aged just eleven and ten years.

Charlotte's sense of loss stayed with her for the rest of her life, and she later immortalized Cowan Bridge as the infamous Lowood School in her novel Jane Eyre.

After the deaths of his eldest daughters, Mr Brontë kept his remaining children close by him at the Parsonage and gave them lessons at home.

“Do you think, because l am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong!”

Branwell died suddenly in September 1848, aged 31. Soon after Emily and Anne became ill. Emily died from tuberculosis in December 1848, at the age of 30.

Anne was anxious to try a sea cure, and in May 1849, accompanied by Charlotte, she set out for Scarborough, where she died just four days later at the age of 29. To spare her father the anguish of another family funeral, Charlotte had her sister buried in Scarborough, then she returned to Haworth alone.

In 1854 Charlotte accepted a proposal from her father's curate, Arthur Bell Nicholls, and the couple were married in Haworth Church. The marriage was happy, although short-lived. Charlotte Brontë died in March 1855, in the early stages of pregnancy.

Mr Brontë lived on at the Parsonage for six years, cared for by his son-in-law Mr Nicholls. He died on June 7, 1861, at the age of 84—having outlived his wife and all of his six children.

After the death of Patrick Brontë, Mr Nicholls returned to Ireland, taking many of the Brontës’ personal possessions with him.

Amanda with our copy of Wuthering Heights purchased at the Museum Shop.

St Michael and All Angels Church, Haworth

Looking at the Haworth Parsonage from the church graveyard.

St Michael's Church has been rebuilt since the Brontë’s attended church here. However, the graves where Patrick buried his wife and all but one of his children, and where he was finally buried himself, were left undisturbed beneath the foundations of the new church, in the approximate place where their family pew was located in the old church,

Anne Bronte died in Scarborough and was buried there by Charolette in St Mary's Church graveyard. Anne loved Scarborough and portrayed it in both her novels Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. She wished to open her own school here.

We were near Scarborough when we visited Whitby; however, we did not make the trip over to Scarborough—mostly because the Scarborough Fair was not happening. Had it been, we would have seen Anne’s grave and picked up some parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme.

The wild and wuthering moorland landscape that was such a great source of inspiration to the sisters.

Patrick Brontë was born in a cottage at Emdale in the parish of Drumballyroney, in the north of Ireland. He grew up within sight of the mountains of Mourne, accustomed to a country way of life, and he developed an appreciation of the natural world at an early age.

When he brought his young family to the bleak village of Haworth in 1820, the wild elemental beauty of the moorlands surrounding their new home cast its spell, and became central to the creative lives of his children.

Despite the influx of tourists, Haworth looks probably much as it did in the early and mid 1800s when the Brontë family likely walked these very pavers.

This building was the Georgian home of the Barraclough family of clock-makers, and Emily Brontë used the name Mosley Barraclough in Wuthering Heights.

The druggist’s house and shop when the Brontës lived in Haworth. The Pharmacist at the time was Betty Hardacre, and it was she who dispensed laudanum to Bronwell in the years leading up to his death in 1848.

The interior of the shop is now beautifully redone. Both the interior and exterior are easily recognizable in the 2022 film Emily.

Bolton Abbey

On the way home we stopped off briefly to walk through one final famous abbey ruin.

These old abbey ruins are all in such beautiful settings!

We absolutely loved the hardware on this door.

Standing where the quire screen once stood.

While the Crossing, Quire, and Chancel were destroyed during the Dissolution, the land owners managed to strike a deal where the Nave was saved and still stands today, serving as The Priory Church of St Mary and St Cuthbert.

The solid stone wall seen at the far east end of the church blocks off what was once the view into the Crossing, with the Great East Window beyond. The fact that part of the original abbey still stands and remains in use, makes this a very unusual ending for a former abbey.

This modern vestibule protects the original west entrance to the old Bolton Abbey.

Meanwhile, back at the car park.